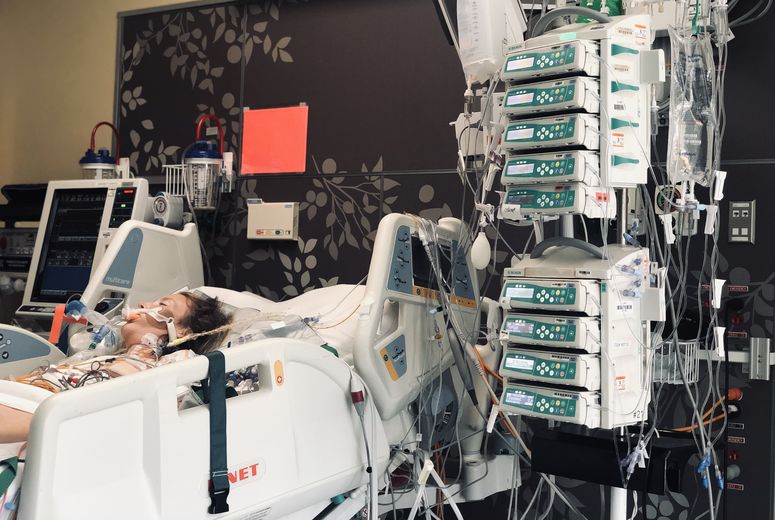

39-year-old Brittany Torres spent months at LLUMC following her diagnosis for peripartum cardiomyopathy and receiving a heart transplant.

For the first time in months since hospitalization, 39-year-old Brittany Torres can walk to her mailbox without a walker, and 31-year-old Lacresha Bell can race her eldest son up the stairs again. Neither of these everyday activities was possible for Torres nor Bell for months after they were diagnosed with a distinctive form of heart failure called peripartum cardiomyopathy. The heart condition can occur during the last few months of pregnancy or up to five months after giving birth.

“I know it may not seem like much, but when you’re once again able to do those things that you kind of took for granted before, and you get to that point where you can do it on your own, it’s such a huge accomplishment,” says Torres.

Cardiac care teams at Loma Linda University Medical Center (LLUMC) provided treatment and helped the women recover so they could return home to their newborn children. Now that Torres and Bell are home for the holidays with their newly expanded families, they hope to share their stories to spread awareness about peripartum cardiomyopathy to other mothers-to-be and their families.

“We need to talk more about this,” Bell says. “I feel like not many people know about peripartum cardiomyopathy, and people need to know that it’s a possibility for them.”

While the National Institutes of Health consider peripartum cardiomyopathy a rare condition because it affects less than 200,000 women in the U.S., it is among the leading causes of death among pregnant women. Its rarity can cause the condition to go underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, says Diane Tran, MD, a heart failure specialist at Loma Linda University International Heart Institute. She says peripartum cardiomyopathy poses serious, even fatal, risks to pregnant women who are not monitored or treated for it.

The other danger with peripartum cardiomyopathy is that its symptoms of shortness of breath or swelling often overlap with those of pregnancy, Tran says. However, Tran urges pregnant women to be vocal about these and other usual symptoms to their care providers, who should listen and investigate further to identify the cause.

When Bell gained 10 pounds in a week during her last trimester and felt shortness of breath, she says she raised the issue to her care team but felt like they “weren’t hearing my complaints as strongly as I was trying to push them through.”

Shortly after giving birth to her son, Bell collapsed in her home and was rushed to a nearby hospital. In March, Bell transferred to LLUMC for a higher level of care when she experienced cardiogenic shock and multi-organ failure.

Read about cardiogenic shock care and LaCresha Bell’s experience: Loma Linda University International Heart Institute sets precedent for cardiogenic shock programs

Bell had recovered enough by June to return home to her two sons. Though still recovering from the four-month hospitalization, Bell says she is glad to be living in her apartment again and return to her job as an accounts clerk for a non-profit.

“Looking at me now, you wouldn’t know that I went through what I went through,” Bell says.

Tran says there were many missed opportunities to properly diagnose and treat Bell's heart failure before her health became life-threatening. Moreover, as an African American woman, Bell was more at-risk of developing peripartum cardiomyopathy and presenting with a more severe case, according to the American College of Cardiology.

“I kind of just fell through the cracks,” says Bell, who hopes that sharing her story will encourage other pregnant women to remain vigilant and vocal about their symptoms and access proper medical care.

Read: Here’s what a patient has to say after two decades of living with heart failure

Like Bell, Torres says her symptoms of peripartum cardiomyopathy were also misdiagnosed; in her case, shortness of breath was chalked up to pregnancy — twice. Torres says she first felt the symptoms of peripartum cardiomyopathy during her fifth child’s third trimester. After giving birth, Torres still felt short of breath when she tried to return to her running routine. By the time she became pregnant with her sixth child, Torres says, “right away, I felt something different,” but her physician again attributed symptoms to her pregnancy.

Her health rapidly declined after delivering her baby in January. After visiting an emergency department for low oxygen levels, Torres says imaging revealed her cardiomyopathy. Then, five months into taking heart medications, Torres began to feel sick again and was referred to Loma Linda University International Heart Institute.

LLU cardiologists deemed Torres needed a heart transplant — her heart was pumping out only 10% of the blood it should be able to pump with each beat. She received a new heart in July, and her latest round of imaging reveals her heart is now working at about 75%. Torres returned to her routine involving raising six children, baking, crocheting, and other activities.

Recently, cardiologist Tran arranged for Bell and Torres to meet one another; they connected over their experiences of returning home and re-adjusting to motherhood, nerve regrowth, and their goals to achieve normalcy and independence.

“It helps so much to talk about it, especially with other people who have gone through something similar,” Torres tells Bell via Zoom.

Both say they are grateful to LLUMC care team members who helped them through one of the most harrowing experiences of their lives and that they’ve survived to spread the word about this condition.

“If our stories can touch someone's life, if one person pays attention and comes out different from this, knowing more or taking care of themselves, it’s totally worth it,” says Torres.

At Loma Linda University International Heart Institute, physicians are committed to providing patients with compassionate, comprehensive, and personalized cardiovascular care. To learn more, please visit lluh.org/heart-vascular or call 1-800-468-5432 to make an appointment.