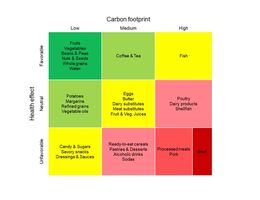

The acacia bush provides food for ants, and in return, the ants protect it from predators.

While venom is traditionally associated with animals like snakes, scorpions, and spiders, a new published study reveals that plants, fungi, bacteria, protists, and even some viruses deploy venom-like mechanisms according to researchers at Loma Linda University School of Medicine.

The definition of venom is a biological toxin introduced into the internal milieu of another organism through a delivery mechanism such as a sting or bite that inflicts a wound. The findings show that reliance on venom for solving problems like predation, defense, and competition is far more widespread than previously recognized.

“Venomous animals have long fascinated biologists that were seeking to understand their deadly secretions and the traits associated with their use, but have also contributed numerous life-saving therapeutics,” said lead author William K. Hayes, PhD, professor of biology for the Department of Earth and Biological Sciences at the School of Medicine. “Until now, our understanding of venom, venom delivery systems, and venomous organisms has been based entirely on animals, which represents only a tiny fraction of the organisms from which we could search for meaningful tools and cures.”

According to the study, It’s a Small World After All: The Remarkable but Overlooked Diversity of Venomous Organisms, with Candidates Among Plants, Fungi, Protists, Bacteria, and Viruses, plants inject toxins into animals through spines, thorns, and stinging hairs, and some also co-exist with stinging ants by providing living spaces and food in exchange for protection. Even bacteria and viruses have evolved mechanisms, like secretion systems or contractile injection systems, to introduce toxins into their targets through host cells and wounds.

Hayes has a long history of researching venom in rattlesnakes, and began exploring a broader definition of venom over a decade ago while teaching special courses on the biology of venom. As he and his team were working on a paper to define what venom truly is, they found themselves encountering non-animal examples and decided to dig deeper to identify numerous examples that may have been overlooked.

This new study paves the way for new discoveries, and Hayes hopes it will encourage collaboration among specialists and scientists across disciplines to further explore how venom has evolved across diverse organisms.

“We’ve only scratched the surface in understanding the evolutionary pathways of venom divergence, which include gene duplication, co-option of existing genes, and natural selection,” said Hayes.

Learn more about the Department of Earth and Biological Sciences.