As a teen, Zoe Gomez loved to do all the typical things girls her age did: hang out with friends, listen to music, play sports, and be a Girl Scout. However, her life was anything but typical due to a rare heart condition called Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA). This condition is undetectable at birth and means that Zoe's left coronary artery was connected to the pulmonary artery instead of the aorta, leading to potential heart failure.

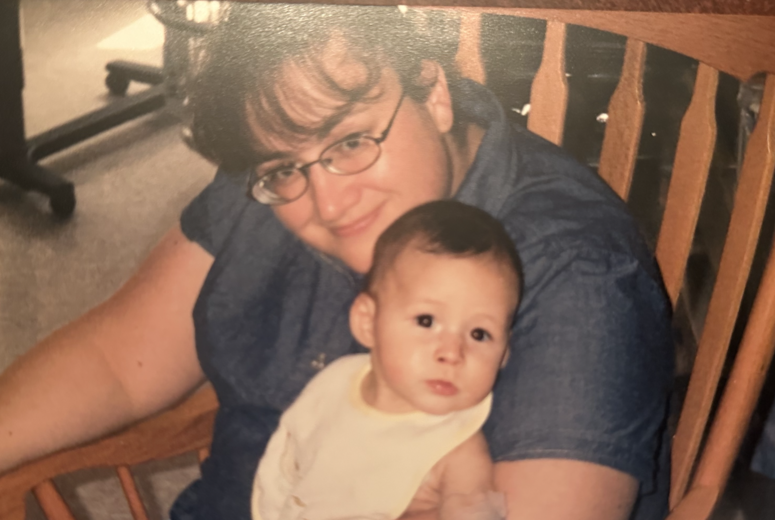

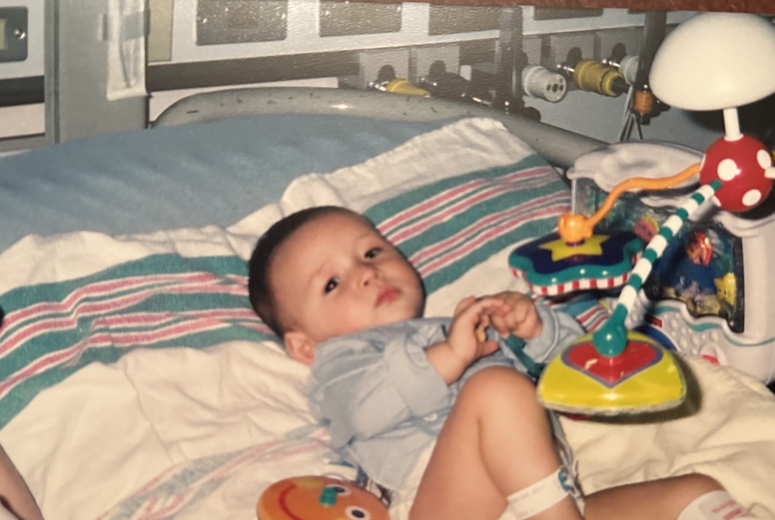

Zoe experienced her first heart attack shortly after birth and continued to have them until she was in heart failure at just six months old. Zoe's mom, Kim Wiser noticed she wasn't breathing normally and looked dehydrated, prompting her to seek medical attention. After being diagnosed at Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Zoe underwent surgery to reposition her left artery. However, after about a year, doctors discovered that her artery was no longer viable.

Over the next three years, Zoe faced heart failures and attacks until her heart adapted to functioning with just one artery.

"Zoe was the complete opposite of the textbook for her diagnosis. She didn't have any of the signs or symptoms. Her condition was so rare that it was typically diagnosed either through a heart murmur, which she didn't have, or heart failure, which she did have," says Kim.

Signs and symptoms of ALCAPA in an infant: Blue/purple gums, tongue, skin and nails, poor weight gain, shortness of breath, sweating or crying during feeding, heart murmur, heart failure.

ALCAPA occurs in 1 of 300,000 live births, according to the National Institutes of Health. Jennifer Newcombe, a nurse practitioner at Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, says patients without treatment rarely survive beyond their first year due to heart failure and myocardial infarction.

"Options for repair include detaching the anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and moving it over to the aorta or creating a tunnel from its abnormal location to the aorta," Newcombe says. “In some cases, the heart is severely damaged and may require mechanical circulatory support with a ventricular assist device or heart transplantation."

Newcome says children with ALCAPA can lead healthy lives with early diagnosis and surgical treatment, though they require lifelong care and may face heart rhythm issues.

Zoe Gomez was awarded the gold award by the Girl Scout 'Gold Project,' for her pediatric to adult cardiology transition of care guide.

Despite her challenging health journey, Zoe now travels internationally, coaches softball, and volunteers with the Girl Scouts. She's a biochemistry student at the University of California Riverside with aspirations to become a pathologist. She has spent a lot of time around healthcare providers and found the profession interesting.

“A heart condition doesn't mean that you're not going to have a normal life, because everyone's normal is slightly different,” Zoe says. “It doesn't define you. You can do anything you put your mind to."

Zoe and Kim found support through the 'Hopeful Hearts Support Group,' a monthly congenital heart defect support group at Loma Linda University Health. The support group meets every third Wednesday of the month from 5-6 p.m. on Zoom and in person, providing a space for families facing similar challenges. The group is led by Kim, Newcombe, and a pediatric cardiology social worker.

For those interested, please contact (909)558-400 ext. 83050, or ext. 43514.

For more information on pediatric heart care, visit online.