When Dung Nguyen describes her one-year-old Charles, her voice softens.

“He’s a fun little kid,” she said. “Very strong, resilient, and funny. He makes jokes, teases, and loves to cuddle. He loves his brother a lot. He loves his family.”

It’s hard to believe that just months ago, this playful toddler spent nearly half a year inside Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, surrounded by tubes, fighting for his life against tuberculosis (TB).

The family had just returned from a trip to Vietnam last summer, where Nguyen’s mother lives.

“We wanted my mom to meet him,” Nguyen said. “It was a fun trip, just family bonding.”

But about a month after coming home, Charles developed a stubborn cough and fever that wouldn’t go away.

At first, doctors thought it was pneumonia. “They gave him antibiotics, but nothing worked,” Nguyen said. “The cough just got worse and worse.”

When his symptoms escalated, coughing through the night and vomiting after feedings, Nguyen insisted on another appointment.

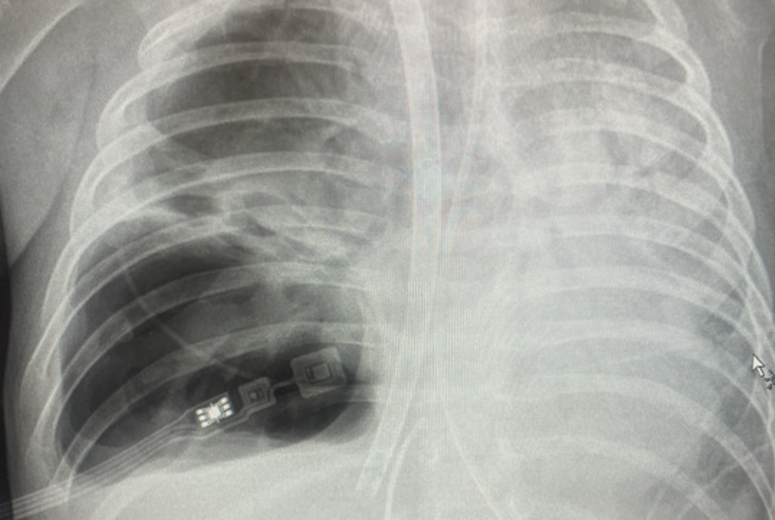

“They took an X-ray and his lungs were all white.”

That night, Charles was admitted to the hospital. Further testing confirmed tuberculosis.

According to the World Health Organization, almost 200,000 children lost their lives to tuberculosis in 2023, most under the age of 5. Many were exposed to TB through close contact.

Active TB can cause a bad cough lasting three weeks or longer, chest pain, coughing up blood or phlegm, weakness, weight loss, and fever.

“He caught TB when he visited Vietnam, and he became very sick very quickly,” said Farrukh Mirza, MD, medical director of the Pediatric ECMO Program and one of Charles’ physicians at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital.

“The ventilators didn’t help him at all, and he went on VV ECMO.”

Understanding ECMO and how it saves lives

ECMO, or Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, is a form of advanced life support that temporarily takes over the work of the heart and lungs. Blood is removed from the body, oxygenated through a machine, carbon dioxide is removed, and the blood is returned to the body. It essentially acts as an artificial heart and lung.

There are two main types:

- Arterial-venous (AV-ECMO): supports both heart and lung function.

- Venovenous (VV-ECMO) primarily supports the lungs.

ECMO care involves a large multidisciplinary team of experts, neonatologists, pediatric intensivists, cardiac intensivists, surgeons, and ECMO specialists, who work together to decide when to initiate ECMO, weighing its risks and benefits. The program unites expertise from three intensive care units (NICU, PICU, and Cardiac ICU) and includes more than 20 physicians and 40 ECMO specialists, comprised of nurses and respiratory therapists trained and available 24/7. Collaboration also extends to administrative and nursing leadership to ensure the highest level of coordinated care.

Historically, ECMO was seen as a “last resort,” used only when all other treatments failed. But today, physicians advocate for earlier intervention before multiple organ failure occurs. Advances in technology, including safer pumps, oxygenators, and tubing, have reduced complications and allowed ECMO to be used more broadly, even for patients once considered unsuitable, such as those with leukemia or severe pneumonia.

For Charles, ECMO became his lifeline twice. “He was on for two weeks and came off really nicely,” Mirza said. "But the destruction of the lung from tuberculosis caused a cavity in his right lung. We then decided to put him back on ECMO a second time and to collapse his lungs completely for about six to eight weeks."

As Charles remained on ECMO, his lungs slowly began to heal. When doctors reopened them, Mirza said, “his lung no longer had a cavity.”

By February, Charles was able to come off ECMO and later the ventilator. “He looks just like a normal baby now,” Mirza said.

For Nguyen, those months were the hardest of her life. “It’s an experience I wish no other mom has to go through,” she said. “There were times I couldn’t imagine a future without him.”

On April 9, after nearly six months in the hospital, Charles was finally discharged. The moment was chaotic but joyful.

“We left the hospital at 10 p.m. and got home around 1 a.m.,” Nguyen said. “It was late, but we were so happy, finally home together.”

Today, Charles spends his days laughing, playing, and cuddling with his parents and older brother. To Nguyen, each ordinary moment feels extraordinary. “Sometimes I remember when he was paralyzed and hooked to machines,” she said. “Now he’s home, smiling and running around.”

Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital has been ranked among the Best Children’s Hospitals by U.S. News & World Report for 2025–2026 — 8th in California and 9th in the Pacific Region, with Pediatric Cardiology & Heart Surgery ranked No. 18 nationally.

Visit online for more information on cardiology & heart surgery at Children’s Hospital.