Ryan Sinclair, right, and a research assistant test wastewater in San Bernardino County.

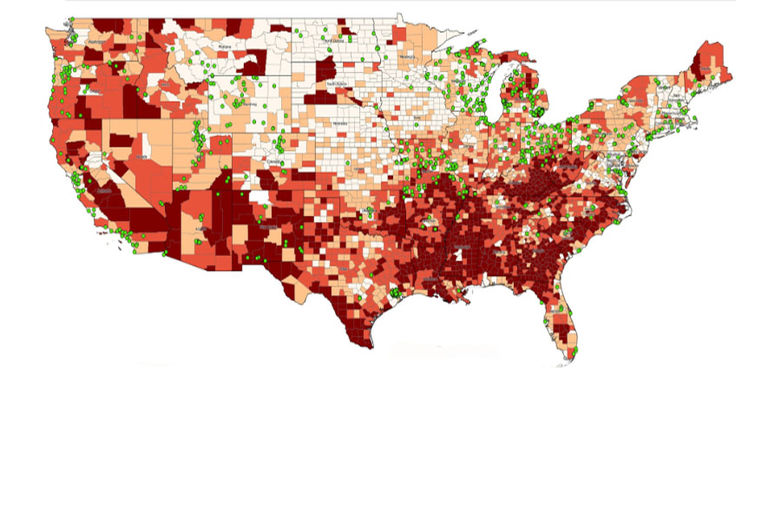

A new study has found that wastewater-based testing of COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States is conducted in inequitable levels, suggesting that a more inclusive strategy with available funding would better protect those in vulnerable populations in future pandemics.

Researchers from Loma Linda University School of Public Health discovered that wastewater treatment plants in low-income areas or that are small and privately owned are less likely to submit testing samples to public health officials. That can leave some towns and state regions less aware of the need to take precautions in a timely manner during disease outbreaks.

The researchers said wastewater tests can be conducted with little or no cost with funding from the CDC National Wastewater Surveillance System or with other local funding.

“Disadvantaged and underserved communities are experiencing what is almost an injustice because they’re simply not getting monitored for disease. And those are sometimes the communities that need it the most,” said Ryan Sinclair, PhD, MPH, associate professor of environmental microbiology at Loma Linda University School of Public Health and supervising investigator of the study.

The study was published in the journal Geographies on February 16.

“These findings offer data to support that a focus on expanding [wastewater-based epidemiology] coverage to underserved communities ensures a proactive and inclusive strategy against future pandemics,” the study stated.

Sinclair underscored that media reports about disease outbreaks are based on data from wastewater, not healthcare facilities like in years past. Samples are collected from wastewater before it enters a treatment facility, capturing data from sinks, showers, and toilets.

Some local wastewater treatment facilities are reluctant to work with public health officials because of lack of funding, or they might be worried about scientists discovering pollutants that their facility may not potentially treat. Sinclair said both concerns are easily mitigated, because public health departments enter into agreements with facilities detailing exactly what in the wastewater will be processed. Health officials are interested in raw wastewater pathogen concentration before treatment.

Public health officials say testing provides communities with information on outbreaks of disease, including COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Wastewater testing can also detect a community’s use of dietary indicators, non-prescription drugs, opioids, or prescription drugs — surveillance information that can help public health departments determine where to focus intervention efforts, Sinclair said.

Funding for the study was provided by Loma Linda University.