This article first appeared in Scope magazine.

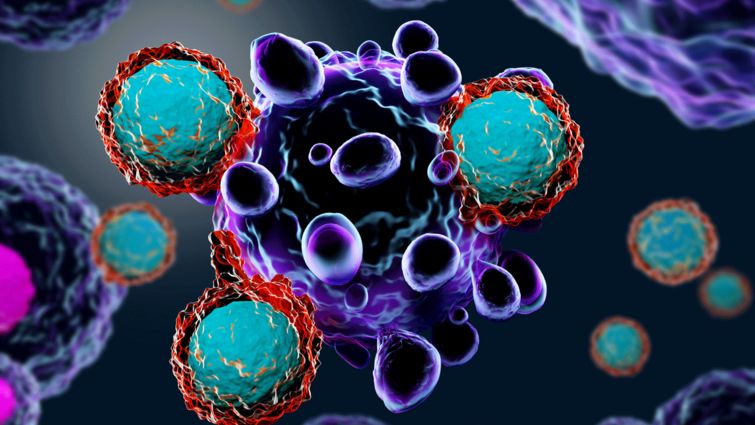

Treatment advances that harness the patient’s own immune system to fight cancer are allowing doctors at Loma Linda University Cancer Center to help people who couldn’t be saved even just a few years ago.

Immunotherapy, which utilizes or enhances various components of the patient’s immune system to fight cancer, has created a paradigm shift in cancer research and treatment, says Mark Reeves, MD, PhD, director of the Loma Linda University Cancer Center. Thanks to this approach, for the first time in the history of cancer treatment, therapies are being deployed and developed that are “site agnostic” — meaning they can treat any and all types of cancer.

As a result, fewer and fewer cancers will be considered a death sentence.

In melanoma, this possibility is already becoming reality; immunotherapy has raised five-year survival rates for patients with a non-operable recurrence from 10 percent or less to 80 percent or above, says Frank Howard IV, MD, PhD, who specializes at the Cancer Center in melanoma and unusual tumors.

“Getting the immune system to fight cancer has been the holy grail of cancer therapy for decades,” Howard says. “It is certainly gratifying to be able to help people I couldn’t help before.”

What’s more, immunotherapy has few unpleasant side effects, making it more tolerable for weakened patients than chemotherapy or radiation.

Immune checkpoint therapy is one of two classes of immunotherapies the Cancer Center is offering, with antibody therapy being the second. The latter injects antibodies specific to the cancer cells into the patient’s blood that focus the immune system on the cancer. Antibody therapy currently shows greatest results in lymphoma and breast cancer.

Checkpoint therapy may actually make patients immune to the return of their cancer, similarly to how people only get the chicken pox once.

Cancer can be so deadly because it rapidly mutates to outsmart treatment. One such mutation destroys a normal cellular pathway called mismatch repair that helps a cell heal itself. Freely replicating in their mutated state, the cancer cells produce abnormal proteins that signal the immune system to back off.

But the cancer cells’ evolved inability to become normal again also makes them vulnerable to checkpoint inhibitors, which are injected into cancer patients and call the immune system back with deadly accuracy against the faulty cells.

“In the future, we will not primarily plan treatment based on location of the cancer’s origin in the body,” Reeves says. “We will ask whether a patient’s cancer has a defect in the mismatch repair pathway.”

Already becoming mainline therapy against cancers that previously lacked effective treatment options, immune checkpoint therapy shows promise not only with melanoma, but also Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, some types of gastric and esophageal cancers, and bladder cancer. It is actually now approved for all cancers that have a defective mismatch repair pathway.

Upcoming in cancer immunotherapy is a combination of checkpoint therapy with vaccines, which is currently in human trials. The double-edged sword is hoped to make cancer cells highly visible to the immune system while also magnifying the system’s cancer-killing power.

For more information, visit the Cancer Center website or call 1-800-782-2623.