Dr. Burruss uses a laser to remove a tattoo on David Loya's face.

Loma Linda University Health recently launched a tattoo removal program to help people efface visible gang-related or anti-social tattoos. The program is part of an endeavor to curb violence associated with gangs for which the Inland Empire region holds a reputation.

Sigrid Burruss, MD, a trauma surgeon at Loma Linda University Health, says lately she has seen more violently injured patients under her care — especially from gang-affiliated altercations. She says she founded the tattoo removal program with the support of Juan Carlos Belliard, PhD, and the Institute for Community Partnerships, to approach the issue from a specific angle; removing patients’ stigmatizing tattoos could help them de-identify as gang members and avoid remaining the targets of repeated assault.

“Trauma teams at the hospital don’t want to see our trauma patients come back from reinjury,” she says. “In addition to fixing up patients in the hospital, we also want to try to address the reasons why they were injured or harmed to begin with.”

Burruss says tattoos are more than ink on our skin; they have the power to signify identity, ideology, and affiliation. Removing gang-related or anti-social and visible on the face, head, neck, or hands can help people protect themselves and embody the self-image they wish to project to the world.

When I look into the mirror, my tattoos remind me of who I was, and I am not that person anymore.David Loya

The tattoo removal program aims to serve those with a history of involvement with gangs, living in poverty, and minority or underrepresented individuals looking to remove tattooed markers of their past to move on, reintegrate back into society, and find employment.

Eligible patients must have completed at least 10 hours of community service through organizations of their choice, homeless shelters, community gardens, or churches. Burruss says the requirement is a way for the program to engage individuals to connect with their community in a meaningful manner.

The program has so far garnered an overwhelming response, Burruss says. Within the program's first few days of operation, over 100 interested individuals reached out with requests and inquiries. Burruss reports that the demand continues to be solid and steady, testifying to the need it is fulfilling within the community.

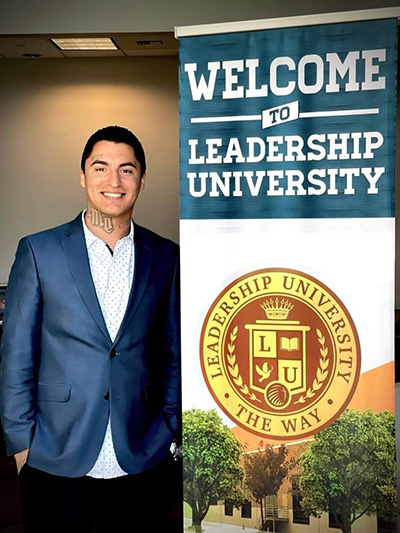

Thirty-four-year-old David Loya, who helps people transitioning out of prison obtain jobs, is one of the patients who has expressed gratitude for the program. He says he is removing his own face tattoos because they don’t represent who he is anymore, and doing so will boost his ability to help his clients when speaking to business owners on their behalf.

“When I look into the mirror, my tattoos remind me of who I was, and I am not that person anymore,” Loya says. “I've noticed that when I talk to people, they see my face, and they are stand-offish. Though they eventually warm up, I want to get the tattoos off my face so I don’t get misjudged and look into the mirror and not be reminded of my past mistakes.”

Loya, who grew up in the Inland Empire, says in adolescence, he "got involved in the streets" and "hung around the wrong people,” leading a lifestyle that came with tattoos, specific dress codes, and substance abuse.

He frequented juvenile halls and prisons for seven years, getting more and more tattoos to express his identity as a gangster, he says. The last time Loya found himself in prison facing a serious sentence at 27 years old, he says he experienced a fateful change of heart: “I was sitting in the prison cell, and I was just tired. I thought, ‘This is not cool. I don’t want this life.’”

Once released from prison, Loya attended a Christian men’s home at The Way World Outreach, where he says he changed his mindset and developed a strong calling to help others. He now works as a leader in his church to help parolees, inmates, and those out of prison transition back into society, obtain jobs, and start businesses. Getting his face tattoos removed was just another step toward being able to help others, he says.

“It feels good. It feels like the right thing to do, and like I’m forgetting the past and moving forward to a brighter future.”

Like many other patients, Loya is returning to the tattoo removal program for multiple visits since wounds must heal for weeks between tattoo removal sessions. He says he is excited to reach the final session and see the outcome.

“I’m thankful for this tattoo removal program because it is helping me erase a mistake that I never thought I could,” Loya says. “I’m happy there is a program for people out there who get a tattoo they wanted, but now they have a different mindset. This program is a solution for that.”

The LLU tattoo removal program is made possible by a team of dedicated nurse practitioners, program coordinator Andre Ike, and funding support from the Institute for Community Partnerships, Burruss says. “Without them, this program would not exist.”

Burruss says tattoo removal programs like Loma Linda University Health’s form part of a greater initiative to support those who need it most in the community. Given the area’s low socioeconomic status and low rates of high school and college graduation, Burruss says it is “not surprising” to see the levels of violence.

“It becomes all of our obligations to approach the issue from many different angles to support and build up the community that we are in,” Burruss says. “This tattoo removal program is one of them.”

Learn more about community outreach and injury prevention at Loma Linda University Health online.To contact the tattoo removal program, email [email protected] or call 909-558-4077.