Linda Olson and her husband, Dave, were adventurers even after the accident that took both her legs and right arm.

This story first appeared in Scope magazine.

Daughter of a pathologist and a nurse at Loma Linda University Health, Linda Olson adamantly avoided trekking the too-well-worn medical career path. Besides, marine archeology or forestry seemed far more exciting endeavors for the then adolescent Linda, who earned her bachelor’s degree in biology in 1972.

Yet, alas, something about the medical field’s promise of usefulness, call of stability, and ever-present demands pulled Linda in says the now 72-year-old Loma Linda University (LLU) School of Medicine alumna and retired radiologist. Because of this career decision and other subsequent twists of life, Linda has found herself in close contact with care providers of all kinds ever since.

“I think it’s a meaningful job. Whatever happens in this world, we will always need physicians," she says. "And boy, did that ever turn out to be true for me."

Can you open a milk carton with nothing but your left hand? Linda Olson certainly can. She finessed the maneuver within the confines of an austere room with a view over the steepled landscape of Old Town Salzburg. This imagery brought her solace during the weeks she spent in that Austrian trauma hospital, re-learning to live a left-handed, leg-less existence.

Whatever happens in this world, we will always need physicians, and boy, did that ever turn out to be true for me.Linda Olson

Linda was three-quarters through her radiology residency at White Memorial Medical Center in Los Angeles and thus quite accustomed to the hospital setting. But this time, she wasn’t in the hospital intentionally. She was supposed to be on vacation. She was there because of the accident.

Only days before her milk carton opening endeavors, Linda, along with her husband and his family, sat in a van. The vehicle rested atop railroad tracks that wound through a lush German forest. Within seconds, a train hurtled down the tracks toward them, crashing into the van and releasing a cacophony of screeching metal.

Linda, who had been crushed by the van in her attempt to escape the event, lost both legs above the knee and her right arm below the shoulder.

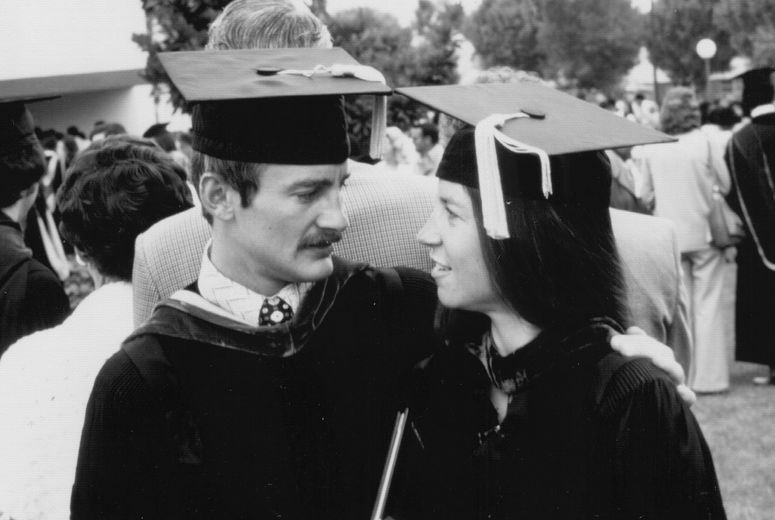

There were no “buts,” no “whys,” no “what ifs,” Linda recalls; there was only “what next?” She and David Hodgens, her medical school sweetheart and husband for two years, determined right away upon their hospital reunion that they would overcome this and live life together.

“We were able to look at it in a very black-and-white fashion,” she says. “Dave told me in the first week that this is the lowest, the worst, we were ever going to be, and that it would all be uphill from here.”

In the wake of their new reality, Dave, who had graduated with Linda from the School of Medicine in 1976, mustered motivation and strength from his daily encounters with cancer patients as a radiation oncologist.

“He had learned so much from watching his brave patients and how they dealt with life-and-death issues that we would be able to survive and excel too.”

Linda says she and Dave were young, strong, and willing to work hard. The two wasted no time, scribbling lists of their daily activities, living needs, and future goals. After all, in addition to LLU alumna, wife, radiology resident, and triple amputee, Linda, whether she knew it or not, had other titles to acquire: mother, award-winning radiologist, professor, wilderness adventurer, and grandmother.

“I was totally absorbed by learning how to do everything differently and anew,” she recalls. “My enormous drive was to be independent again. If I could go back to being normal, then it didn’t matter.”

So, Linda faced the first steps. She learned to walk in full-length prosthetic legs — a tricky ordeal she describes as walking on stilts with a knee. Even putting the prosthetics on was its own challenge. But eventually, with hours of training, David’s unwavering support, and a pair of prosthetic legs under her belt, Linda walked back through White Memorial Medical Center’s automated doors to complete the final nine months of her residency.

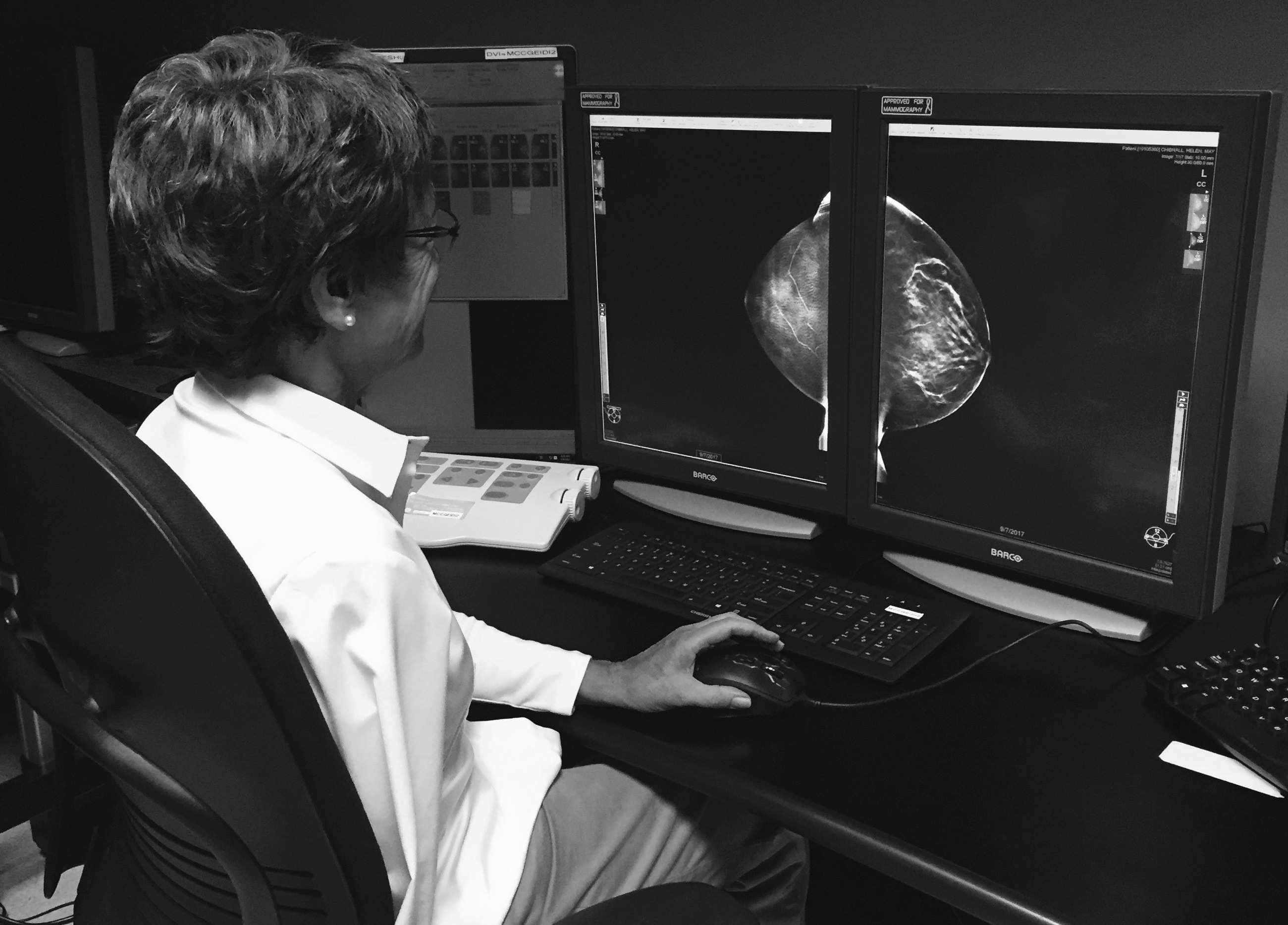

Life moved fast. Together, Linda and Dave raised two children, Tiffany and Brian, in a home they’d designed to accommodate their lifestyle and needs. She launched what became a 30-year career of radiology practice and professorship at the University of California, San Diego.

She specialized in pulmonary radiology and breast imaging and treasured teaching the beginners, relishing those moments of “watching things dawn on somebody’s face.” As a “people person,” Linda also loved interacting with the bustling network of clinicians, faculty, and doctors. She amusedly reports that some colleagues and students hadn’t even noticed her legs were missing until recently.

Their unconsciousness may be in part, she says, due to a tactic she adopted early on in the hospital in Salzburg to communicate with people, so they did not fixate on the nature of her disability.

“There’s a trick to talking to people,” she says. “You have to look at them and engage them with your eyes. As soon as their eyes meet your eyes, they will start concentrating on that connection. If that connection happens, a lot of people don’t recognize what’s really going on below the neck.”

However, the case was slightly different on certain hikes and outdoor adventures, like in Machu Picchu, Peru, when Linda rode in Dave’s modified pack frame and passersby stole double-takes at the mysterious two-headed hiker.

Linda recounts these moments and many others in her first book, “Gone: A Memoir of Love, Body and Taking Back My Life,” published last year. She says she waited almost 40 years after her life-changing event to write the book so she could rack up enough proof to demonstrate the completion of a successful career and family life as a disabled person.

“The commitment Dave and I had to each other is really the beauty of the whole story and one of the main reasons I wrote the book,” she says, “This is a love story. We did this as a team.”

In the pursuit of a normal life, Linda says she initially avoided the limelight, turning down media opportunities and requests for talk show appearances. She did, however, offer low-profile talks to trauma and emergency department care teams to convey that their hard work could save and enable people like her to lead happy, productive, fulfilled lives.

But in recent years, as Linda has been mitigating the effects of Parkinson’s disease, she has spoken to audiences in the Parkinson’s community about leading a successful, action-packed life as a disabled person. Inspired by the abundance of positive feedback, Linda plans to continue sharing her life experiences to communicate, “it doesn’t matter if you look funny, or if you can’t use your hands, you should go out and have a good time.”

“If after hearing my experience, people can go home and tell themselves ‘if she can do it, I can do it,’ then it’s all worthwhile to me.”