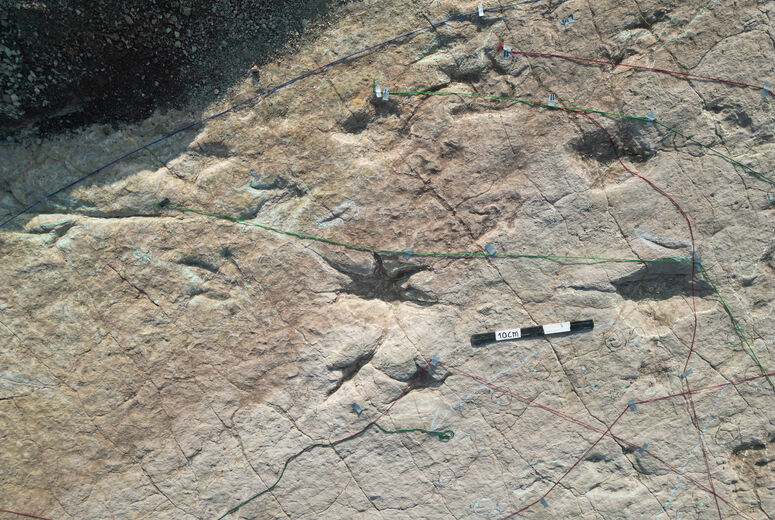

A team of paleontologists, including Loma Linda University faculty and students, has identified the world’s largest known site of dinosaur trackways, located in an isolated region of the Bolivian Andes. Their examination of 16,600 dinosaur tracks is a landmark study in vertebrate ichnology, which is the study of fossil traces.

Researchers stated that the tracksite in Torotoro National Park contains dinosaur footprints, swim tracks, and tail marks, each in abundance unmatched at any other dinosaur tracksite worldwide.

One key finding was that theropods, which were carnivorous dinosaurs, mostly walked rather than ran — contrary to what is often shown in movies. Researchers said only 1% of the tracks showed a dinosaur running.

“Paleontology now has a huge statistical database of footprints, swim tracks, and tail traces, which allows statistical calculations that teach us about the locomotion and movement behavior of these animals,” said Raúl Esperante, PhD, the senior author on the study. Esperante is a senior scientist at the Geoscience Research Institute, a Seventh-day Adventist organization headquartered in Loma Linda, and an adjunct professor in the Department of Earth and Behavioral Sciences in the School of Medicine at Loma Linda University.

Another finding was the direction of the trackways. Dinosaurs walked on what is now known as the Carreras Pampa tracksite in two main directions — north/northwest and south/southeast. The orientation pattern of the trackways indicates that the trackmakers traveled in groups, possibly during migration, in search of food or to escape a natural disaster.

The team also found more tail traces than all other parts of the world combined. Many of those traces are winding grooves that link several footprints, showing that the animals sometimes lowered their tails and dragged them, possibly to stay balanced on soft ground.

The study was published earlier this month in the journal PLOS One.

Esperante said he estimates the site may have as many as 25,000 tracks, based on photogrammetric models derived from photos that reveal tracks invisible to the human eye.

The team also found preserved swim tracks alongside walking tracks, which is highly unusual, Esperante said. Swim tracks have been discovered in several parts of the world, including the United States, China, Spain, and a few other countries. Esperante said the significance of the Carreras Pampa swim tracks is that they occur in trackways tens of meters long, a pattern preservation that provides information not possible to obtain from other tracksites.

The study included multiple expeditions over five years, with roughly eight months of fieldwork and additional months dedicated to office and lab work. The research team comprised about 20 people across different expeditions. Researchers came from North America, Europe, and South America.

Esperante said the study, which is 164 pages long, is a culmination of presentations he has delivered about the tracksite at paleontology conferences worldwide over the past five years. Kevin Nick, PhD, from the Department of Earth and Biological Sciences at LLU, has contributed significantly through field work and writing to the research. Additionally, the research team includes students from Loma Linda University and universities in Argentina, Chile, Spain, and Brazil, as well as early-career professionals from several countries.

Esperante said he was proud of the way the team interacted with the Bolivian residents, gaining support of farmers, park guides, and small shop owners who live in the remote region. Each expedition concluded with a two-hour presentation to the community on what the team had discovered. That was followed by a site visit where researchers showed the site and discussed preservation. The engagement with the local population in education and preservation has been key to the success of the investigation, Esperante said.